Prompt of the Day #4

Imagine that you or a character has just come home from the longest journey they've ever made. Think about their immediate reactions to being home - relief, joy, worry, distaste - think about how they might narrate their story to friends and how it might change over time. How do they feel after the initial return - content, restless, excluded, changed?

When Homer wrote the Odyssey, the protagonist, Odysseus has set sail from Troy after the happening of the Illiad, and is trying to return to his native Ithaca after ten years of war with the Trojans. His voyage, which should have taken a couple of weeks, takes him ten years. In those ten years he battles monsters, listens to Sirens, meets and 'befriends' two beautiful Goddesses: Circe and Calypso, blinds a Cyclops, travels to-and-from the Underworld, loses all of his comrades, wanders from civilisation to civilisation and eventually returns to discover his wife is being pressured by a bunch of irksome suitors trying to usurp him from his rightful throne. As an epic poem it has been one of the most influential pieces of literature in Western canon, inspiring hundreds of writers from the other much lauded Classic: Virgil, to Shakespeare and James Joyce. In fact, poets such as Tasso and Spenser, who both wrote Christianised epics, followed very closely to the themes and even the language of Homer, recreating almost the entire Odyssey albeit with characters plucked from morality plays. Similarly, if I was going to bore you into a blob of vapid expression, I would list the huge number of poets that have taken twenty lines of the Odyssey (or the Aeneid) and turned them into page long poems.

The influence of the Classical Epic is phenomenal and it is characterised by voyage. Not just any voyage mind you, but long, never-ending, traumatising, life-destroying, character-building voyages. Christopher Booker even acknowledges this as an archetypal example of one of The Seven Basic Plots: Voyage and Return. Many fantasy novels are based on this idea - take the Lord of the Rings, or the Belgariad as examples. In these, 'The Quest' may start as the general premise, they may have to 'Overcome the Monster', there may even be hints of Comedy, Tragedy, Romance etc but ultimately the 'Voyage and Return' is the overwhelming plot for the story. Why? Because a voyage, like an epic, can encompass hundreds of different ideas and emotions and can reflect both literal and metaphorical transformation. With Odysseus, he desperately wants to go home, but he has to overcome dozens of trials in his wanderings. With the Red Cross Knight or the Knight of Termperance (The Faerie Queen, as inspired by Homer), these figures have to encounter the thing that most tempts them, their apposite character, in order to really become the embodiment of a virtue. Voyage, in allowing a character to travel from place to place, also allows them to develop through obvious challenges, to triumph and fail and gives the writer free reign to examine a plethora of human emotion.

The Return is equally important. Of course, the joy of arrival for Odysseus is somewhat dampened by the fact that he has to disguise himself in order to judge the loyalty of everyone he has ever known - the slave woman that nursed him as a babe, his wife, his father etc. Furthermore, he has returned to discovered he is MPD and his wife is being heckled by a number of lascivious old aristocrats. He promptly smites them, intending to remind you of how he is both Odysseus the Wanderer but also a hero of Troy but he still has to go through the trial of Revelation and after all this, he finally, truly 'Returns'. Inspiration, can come from the different monsters he fights (ie. The Lotus Eaters), the different people he meets (ie. Circe), the great and ridiculous 'weeping', the moments of intense ekphrasis... the list goes on.

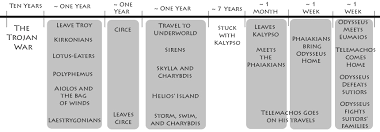

Tennyson's poem 'Ulysses' is one example of how a writer uses a classical text to inspire his own writing. Tennyson, despite not having such a helpful manual as Booker's explanation of plot, considers the character of Odysseus/Ulysses and using the voice of the hero himself, imagines what the man thought of his life twenty years on from The Return. So if this is the traditional timeline for Odysseus:

Then add another twenty years on with Odysseus back as king of 'barren' Ithaca and you can imagine how he might be feeling. He had ten years of war, ten years of voyaging and then the following years of peace. Tennyson, who also rewrote the scene with the Lotus-Eaters, created a scene where Ulysses seems to want to return to the life he lived as a traveller, as famous hero surrounded by myth instead of fact. Yet the narrator also seems reminiscent of the Sirens, who promised him both fame and 'knowledge ... beyond human understanding', often described as mantric truths. This is Tennyson's 'gray spirit yearning in desire/ To follow knowledge like a sinking star,/Beyond the utmost bound of human knowledge.' His creation is one that is no longer content with the 'still hearth' and 'barren crags' or the 'aged wife' he fought for in the original epic. This is a character who seems to have carried the temptations of the Siren song home with him, has become obsessed with it, who has romanticised the 'dark broad seas' so that even Charybdis's gaping mouth and Circe's idyllic island become an equally enticing adventures.

It's almost as if Ulysses is going through a mid-life crisis. As the fear of being 'made weak by time and fate' juxtaposed to the idealised 'old days', remains emphasised throughout the poem, we initially imagine that this character is sincerely desirous of the travelling life because he is ageing, realising his increasing impotence as his son takes over the rule of Ithaca. Yet, due to the hints towards the sirens that he alone heard, we are also encouraged to doubt, to read with a pinch of scepticism, a slither of active readership. Why are the 'gulfs' that 'wash ... down' and the 'Fortunate Isles' are juxtaposed against each other as similarly lauded adventures? Is the poem really about literal travel? Does he really want to return to a 'newer world' or are the references to age, the 'end', seeing 'the great Achilles' actually suggesting that Ulysses is ready to embark on the last adventure, into death itself? Or does the final sentiment that determines 'not to yield' imagining that he is desperate to cling to life, to return to life? Does the siren song promise him an escape through life or through death? And is Tennyson being serious with all of this? These are all questions that we can play with.

Tennyson, doesn't just use very deliberate allusions linguistically but he also uses meter to emphasise the conflicting rationales behind the narrators opinions. This is particularly evident with the use of spondees in the lines, slowing them down as if the narrator is luxuriating in them, emphasising the sense of idealism, whereas the following line uses a trochiac opening to accentuate the feverish fervour of his excitement. Against a predominantly iambic poem, lines like these are striking, lending a sense of strangeness that suggests that maybe the character is not entirely in his right mind.

You can read a poem like this in dozens of different ways. I tend to read it ironically. But what we all have to see is how Tennyson uses a familiar trope and a well-known story and develops it into his own, expressing something that is ultimately very personal and unique to his time. A new perspective on a hero can usurp convention. In this case it's the opinion that once the story is concluded, the voyage complete, the return celebrated, things will right themselves. In the case of the Odyssey, we're even guaranteed an end to his tribulations through the use of deus ex machina. Yet Tennyson's poem reopens the page for us.

When you're creating a character, think about how you're developing him/her. Consider what journey your character is going to go on, whether it be literal or internal and think about what sort of person they are, not only in the past but in the future.

Je serai poète et toi poésie,

SCRIBBLER